sabilarthouse

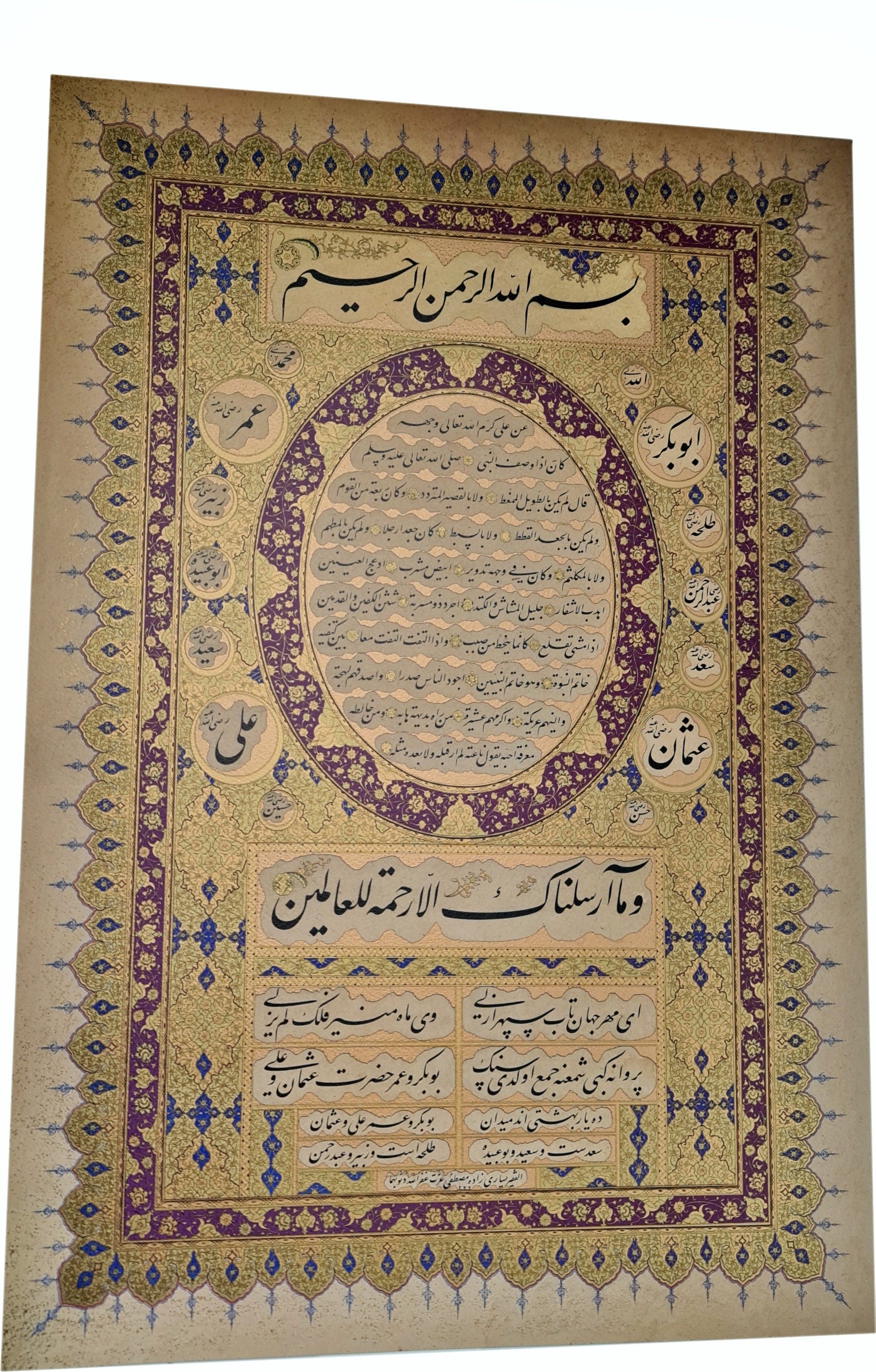

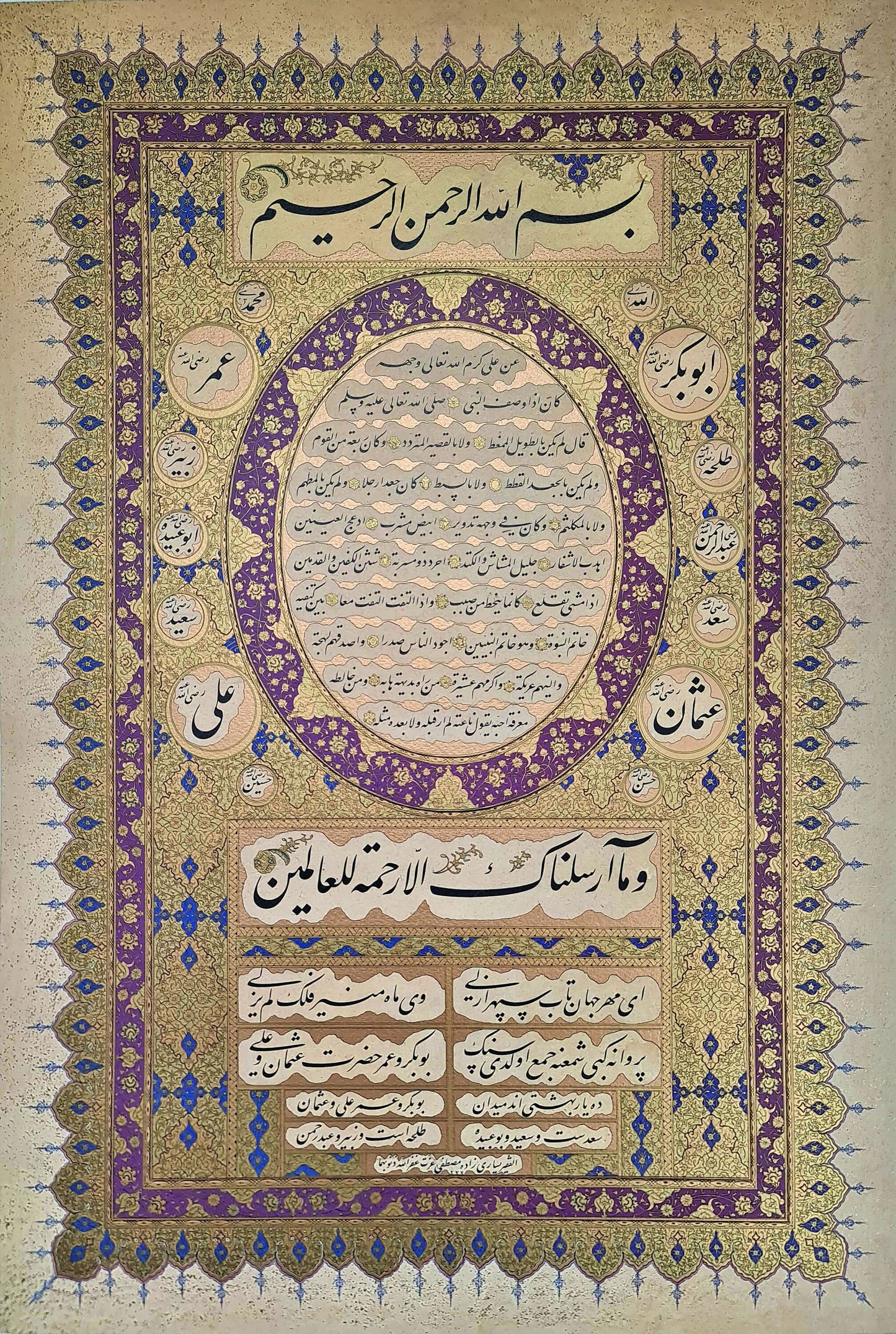

Ottoman Hilye-i Şerife in Nastalik script | Limited edition reproduction of work by Yesarizade Mustafa İzzet | Beautiful Islamic art

Ottoman Hilye-i Şerife in Nastalik script | Limited edition reproduction of work by Yesarizade Mustafa İzzet | Beautiful Islamic art

Couldn't load pickup availability

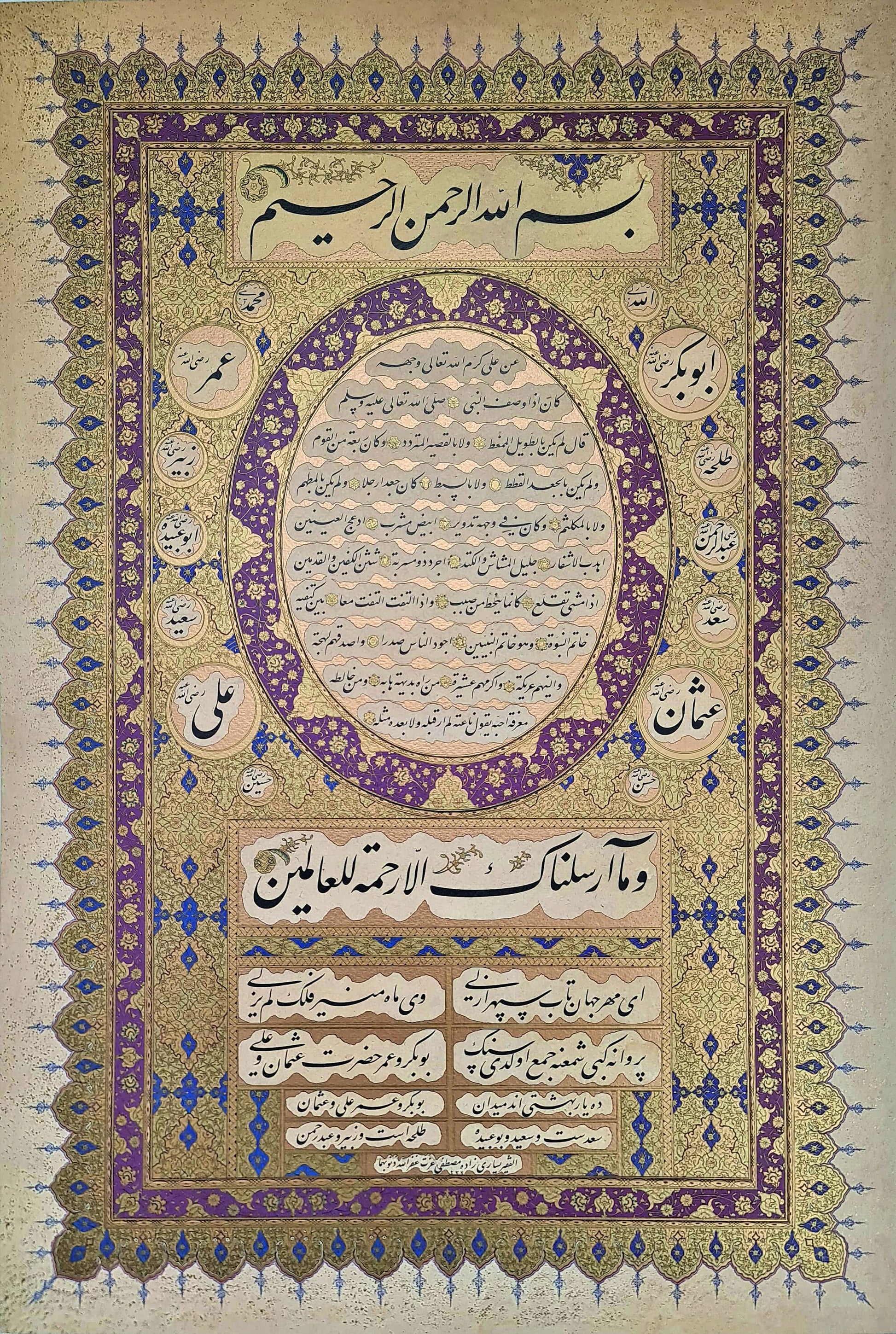

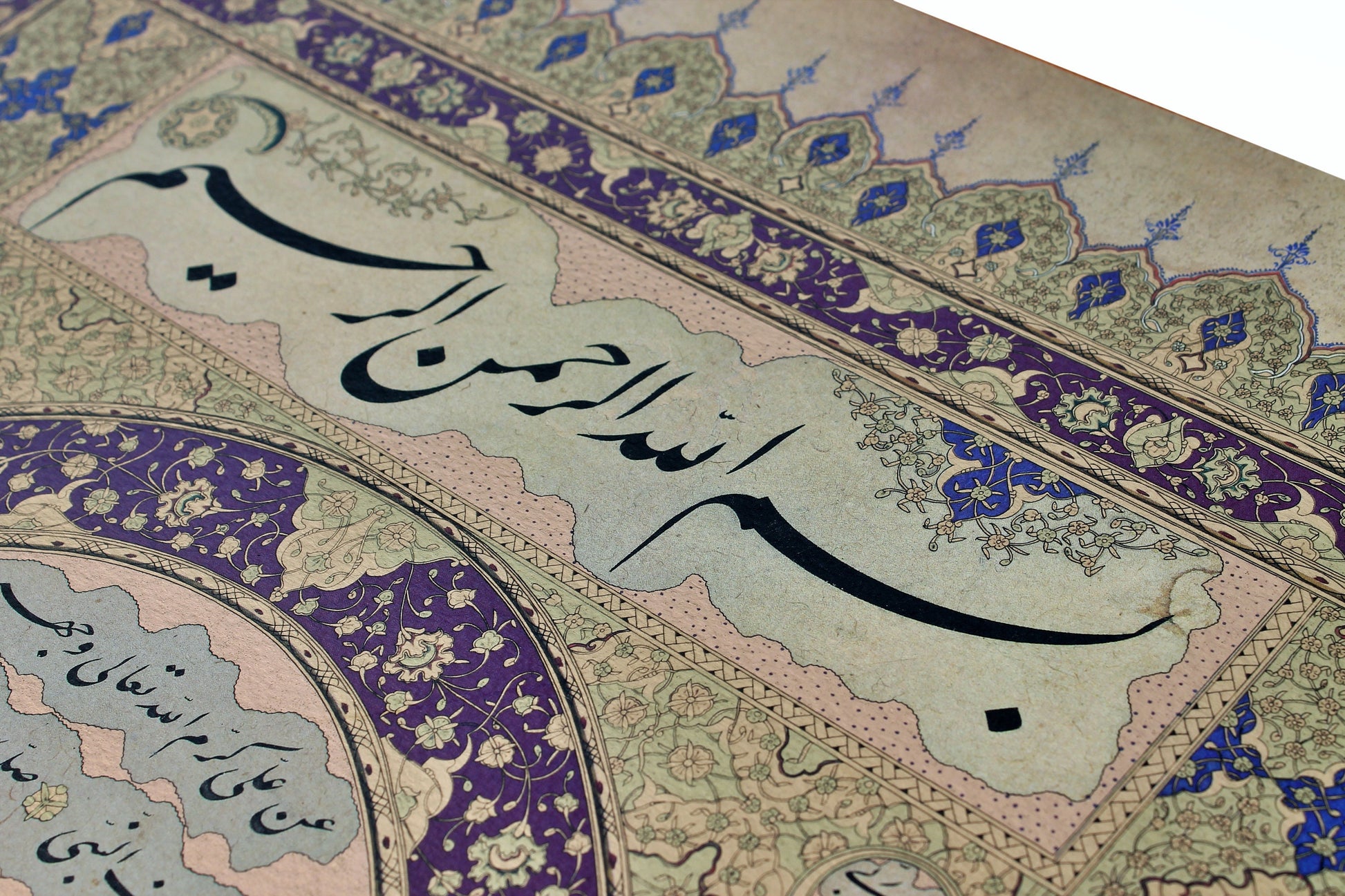

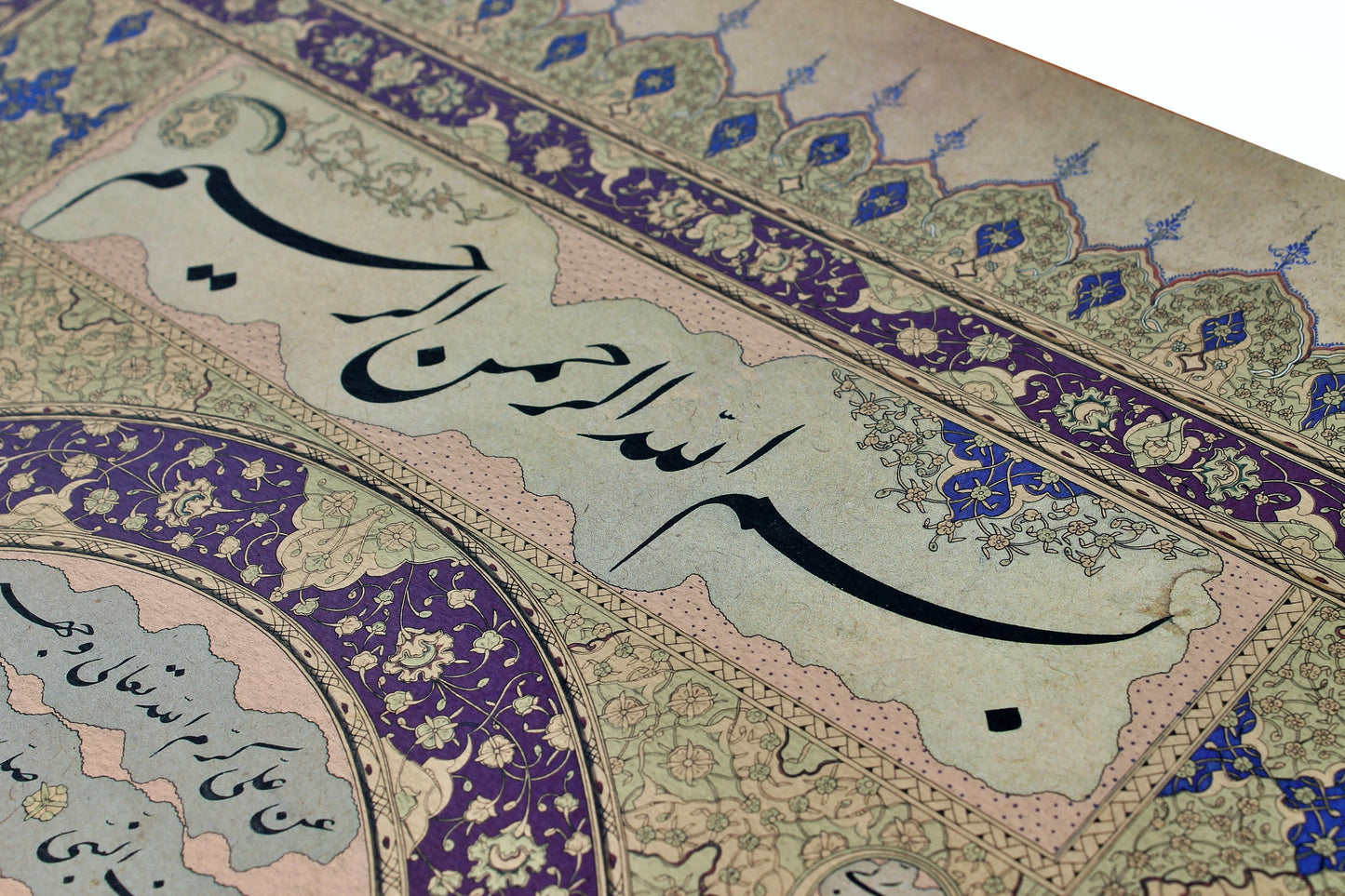

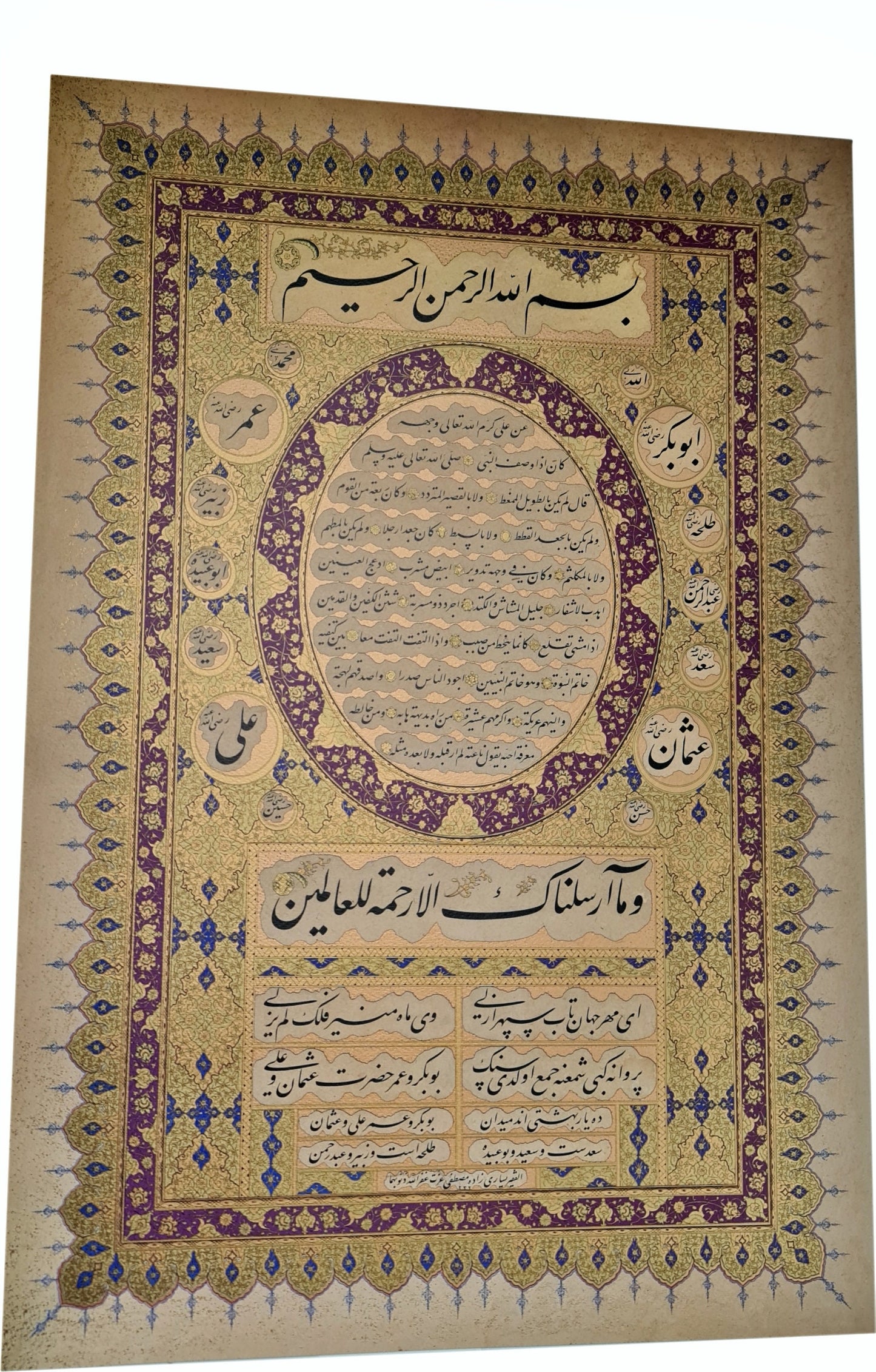

This lithographic print reproduces a remarkable Ottoman-era hilye (verbal description) of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ. The original piece was composed in stunning nastaliq script by the master calligrapher Yesarizade Mustafa İzzet in 1233 AH (1817-18 CE).

At the head of the work is the basmala, while the main text, which is found in the large, central roundel, contains a hadith from the collection of Imam al-Tirmidhi that has been narrated from Imam 'Ali (may God be pleased with him). The hadith describes the physical qualities of the Prophet as well as his noble characteristics:

[Narrated] from Ali, may God honour him, when he described the Prophet (ﷺ) he said: He was neither very tall nor excessively short, but was a man of medium size. He had neither very curly nor flowing hair but a mixture of the two. He did not have a large body. He did not have a very round face, but it was so to some extent. His complexion was reddish-white. He had wide black eyes and long eyelashes. He had large joints and the portion between the two shoulders was broad. He was not hairy but had some hair running from the chest to the navel. He had thick palms and feet. When he walked he raised his feet as though he were walking on a slope. When he turned round he turned completely. Between his shoulders was the seal of prophecy, and he was the seal of the prophets. He was more generous in spirit than anyone else, truer in utterance, gentler in nature and nobler by tribe. Those who saw him suddenly stood in awe of him, and those who shared his acquaintanceship loved him. Those who described him said they had never seen anyone like him before or since [Adapted from the translation of Tim Stanley in 'From text to art form in the Ottoman hilye].

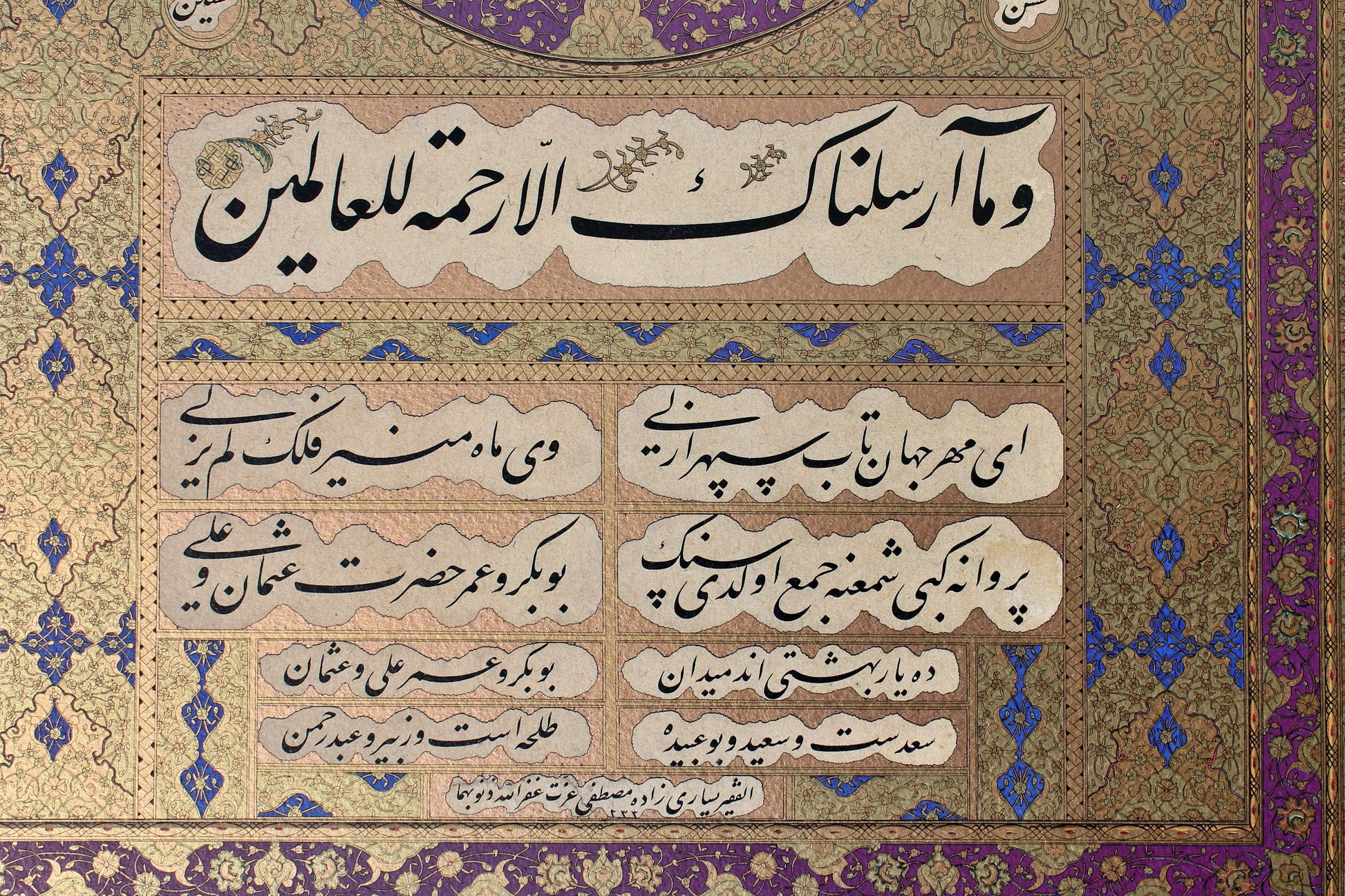

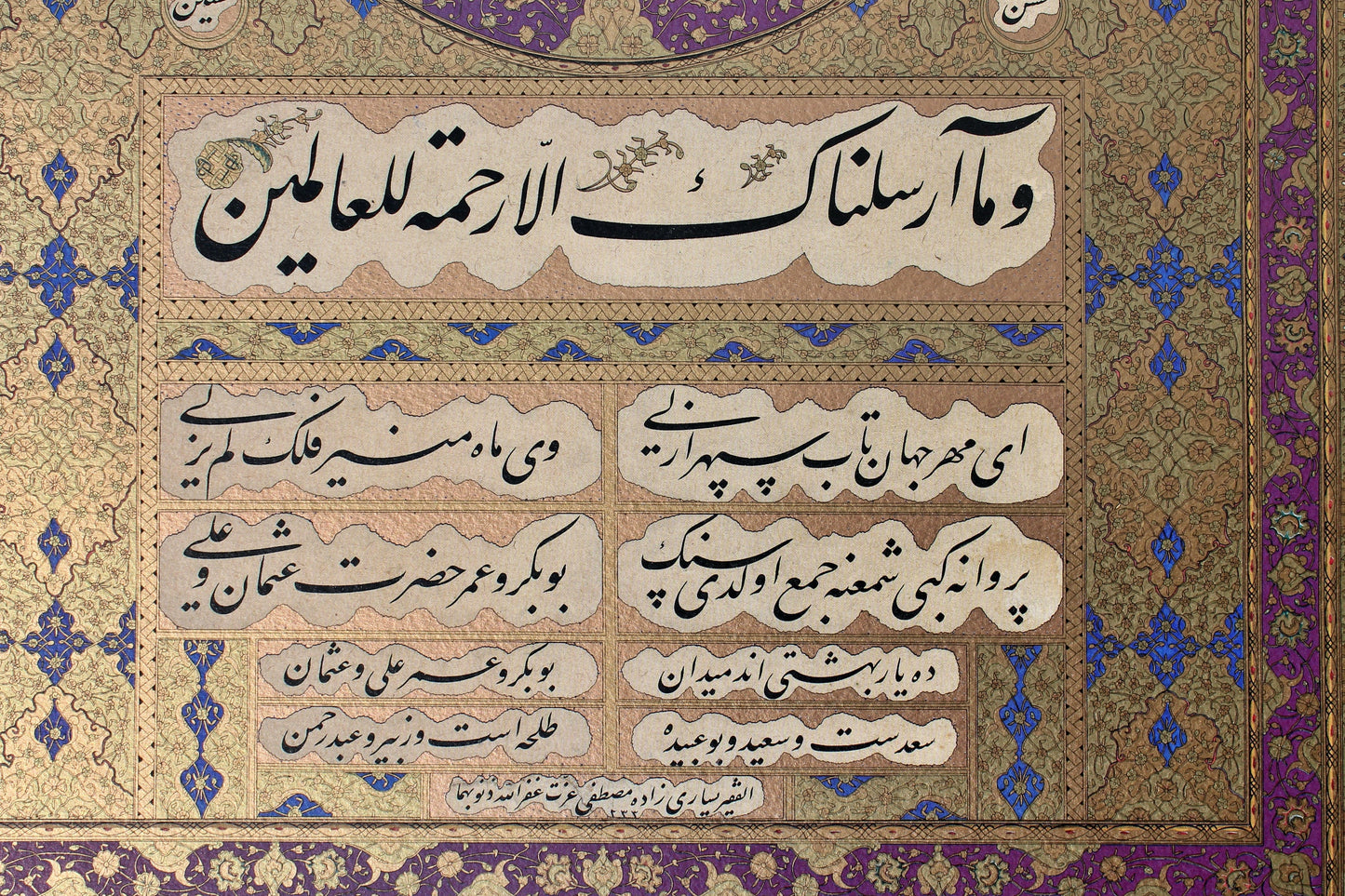

Surrounding this larger roundel are ten smaller roundels carrying the names of the ten 'Asharat al-Mubashsharah, the 10 Companions of the Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ) who were promised Paradise. The roundels carrying the names of the four Rightly-Guided caliphs (Abu Bakr, ʿUmar, ʿUthman, and ʿAli) are slightly larger and feature in the four corners around the center.

Below this is verse 21:107 of the Qur'an, 'It was only as a mercy that We sent you [Prophet] to all people.' Yesarizade Mustafa's hilye also includes beautiful verses of Ottoman Turkish poetry in praise of the blessed Prophet and mentioning once again the ten who are promised paradise in poetic form. The calligrapher's signature can be found at the very bottom of the work: 'The poor, needy one (al-faqir) Yesarizade Mustafa 'Izzet, may God pardon his sins. [1]233'.

===============

Limited edition high-quality lithograph print (300 copies)

Size: 673 x 463 mm.

Calligrapher: Mustafa İzzet

===============

Yesarizade Mustafa İzzet

Mustafa İzzet was born in Istanbul, though his exact date of birth is unknown. It can be said that he was born in the early 1770s, considering that he received his license (ijaza) from his father, Yesari Mehmed Esad Efendi, in the ta'lik script in 1202 AH (1787-88 CE) and went on the hajj with his father in 1792. His ijaza was ratified by Mehmed Emin Bey in the same year it was given to him by his father, as well as by Osman el-Uveysi in 1203 (1789). He became Anatolian kazasker (military judge) in 1839 and also oversaw the printing press known as the Matbaa-i Âmire. Mustafa İzzet Efendi was then appointed to the position of Rumelian kazasker in 1846, and died a few years later on 2 Şaban 1265 (23 June 1849). He was buried next to his father in the small burial ground in the Tûtî Abdüllatif Efendi Medrese, which was located near the Fatih medrese.

A history of the Ottoman Hilye

Initially, the word ‘hilya’ (Turkish: Hilye) referred to the various hadith which describe the beautiful physical appearance and moral character of the Prophet Muhammad. Many of these are found in the ‘Kitab al-Shama’il’ of Imam al-Tirmidhi (died 279 AH/ 892 CE), which was the earliest collection of its kind.

The first person to present the hilye as a calligraphic art form was the Ottoman master calligrapher Hafiz Osman in the later 17th century. He based his work on a famous hadith from the Shama’il. The earliest examples of calligraphic hilyes all carry the name of Hafiz Osman, and together, they show that by the end of the 17th century, Ottoman Muslims had begun to hang verbal portraits of the Prophet Muhammad on their walls. These descriptions were often combined with verses from the Noble Quran.

The basmala at the top of the hilye indicates the position of God above all things. Beneath this is a large rectangular zone (a large roundel surrounded by smaller roundels) which describes the Prophet and mentions the names of those closest to him in rank. The placement of the Rightly-Guided caliphs (and occasionally Hasan and Husayn and/or the Asharat al-Mubashshara) in smaller roundels parallels the monumental wooden panels that were erected in major Ottoman mosques, perhaps most famously the mosque of the Hagia Sophia.

The Prophet's own description in a large circular roundel invokes the similarly shaped sun and moon; the rising sun and the new moon are fitting similes for the Prophet’s beauty. Following this is a third section, featuring a verse from the Quran which refers to the Prophet as God's messenger to all people. Thus the middle section (between the basmala and the verse) can be seen as a zone intermediate between God and humanity, which befits the Prophet’s station as a messenger sent by God and an intercessor on behalf of his umma.

The final elements in the layout of the hilye usually identify the name of the scribe and the date of completion, which is the lowest position on the panel, and which well represents the humility of the calligrapher, who often identifies himself as al-faqir, one who is poor and destitute, and beseeches God to forgive his sins.